Dear audience, continuing from the previous post, my junior brother will now talk about my banking experiences before entering Web3, mainly memorable lawsuits and an anecdote about a fallen Forbes magnate, as well as some impulses and reflections on why I left the banking industry.

Many people assume that returning from an overseas oilfield job to join a bank means a stable career path, but the first thing I did at the bank was not writing credit reports or disbursing loans. Instead, I went alone to the Guangdong Provincial High Court to sue and clean up potential bad debt, targeting a listed oil company at the time—somewhat related to my background.

The Guangdong Provincial High Court has a very high step, giving a strong sense of solemnity and harsh reality. I carried a bag while the lawyer lugged a huge suitcase of files: contracts, supplemental agreements, loan notices, inquiry letters, minutes, statements, even the controlling shareholder’s marriage certificate. Each page was like a thumbtack; I had to pin the entire money trail onto a timeline to ensure public funds didn’t slip away.

After entering the courtroom I foolishly plopped down on the plaintiff’s side. The judge asked, “Do you have bank authorization?”

I replied, “I haven’t received it, Your Honor, this is my first lawsuit—what authorization do I need?”

Judge: “Without authorization you have no right to attend this hearing. Take a seat in the gallery.”

So I obediently moved to the side and watched the lawyers trade arguments. The second lawsuit was in Hangzhou, against an elevator manufacturer. Because the case was eight years overdue (I even suspected the boss sent me to get practice), I ended up with an unreliable lawyer. The judge asked in court whether the physical evidence was ready; the lawyer said, “Wait, let me look,” and spent ten minutes flipping through files while everyone stared. The defendant’s counsel—an older woman—said, “Hurry up, I have something to do after this.” Eventually the judge, fed up, told the plaintiff’s lawyer to prepare the evidence before making any claims. I was completely stunned, awkwardly fidgeting. Fortunately both lawsuits were resolved smoothly. The oil‑company case was withdrawn and extended (oil prices recovered, and the purchased fixed assets appreciated), but every penny of the costs was still incurred. (A side note: the department head who handled this business later left, heavily invested in FIL miners, and now runs a coffee shop.)

During that period I often wondered: after returning from Iraq and Venezuela, I wanted to join a more stable system. Yet the stability I entered placed me at the courtroom door, holding a stack of papers proving “money is indeed money.” That was my first impression of banks: at the core of centralized finance, it’s not efficiency but control; not liberty but compliance; not growth but accountability.

Later I gradually followed my mentor, mainly handling buyer‑side credit under China Export & Credit Insurance’s “Double‑95” (95% coverage for political and commercial risks) and some low‑risk domestic credit. The most interesting low‑risk client was a heavyweight in the metal industry, often featured in mainland Forbes Top‑20. He later fell straight down. Knowing his business model made his downfall unsurprising—after all, we were the ones who actually knew how much money he truly had; Forbes isn’t always accurate, and identity abroad is self‑crafted. That’s certainly true, and later…

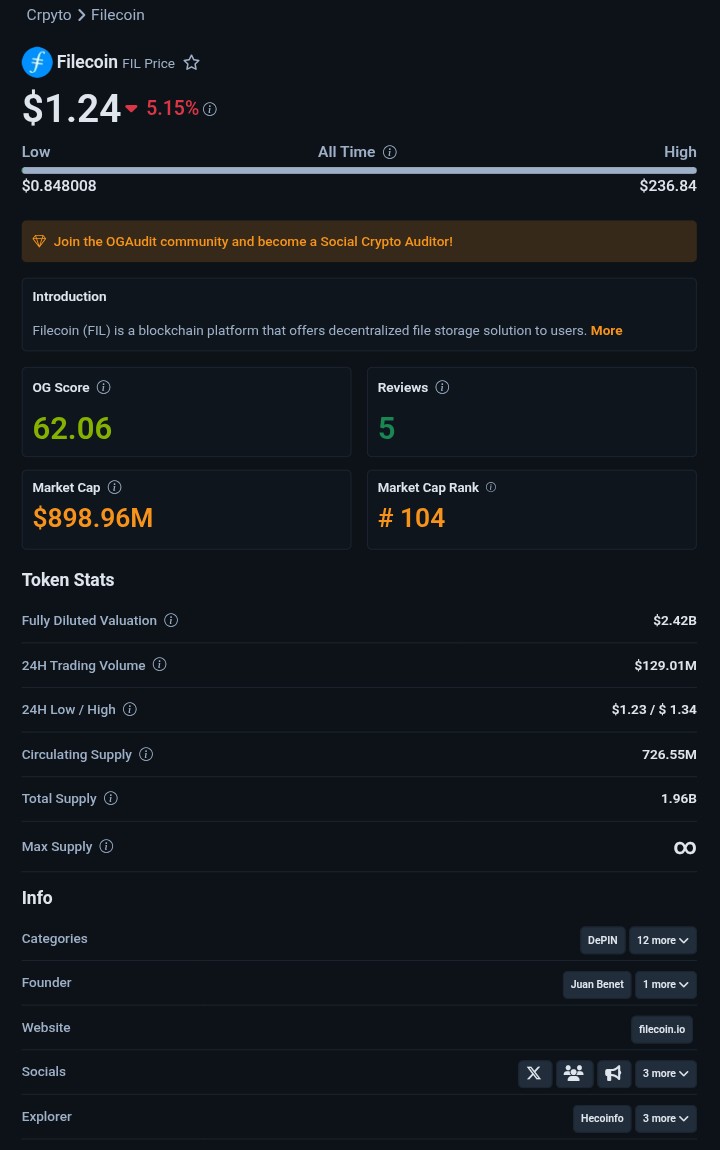

Filecoin (FIL)

Filecoin (FIL) StefanB TA_Analyst Trader B27.88K @Stefan_B_Trades

StefanB TA_Analyst Trader B27.88K @Stefan_B_Trades

StefanB TA_Analyst Trader B27.88K @Stefan_B_Trades

StefanB TA_Analyst Trader B27.88K @Stefan_B_Trades 24 2 5.48K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish

24 2 5.48K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish DinhTien | 🎒 Community_Lead Educator B8.87K @DinhtienSol

DinhTien | 🎒 Community_Lead Educator B8.87K @DinhtienSol Filecoin D663.52K @Filecoin5.31K 168 196.15K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseNeutral

Filecoin D663.52K @Filecoin5.31K 168 196.15K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseNeutral Jeremy Allaire - jda.eth / jdallaire.sol Founder Tokenomics_Expert B167.64K @jerallaire

Jeremy Allaire - jda.eth / jdallaire.sol Founder Tokenomics_Expert B167.64K @jerallaire Coinbase Developer Platform🛡️ D56.03K @CoinbaseDev192 8 18.01K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish

Coinbase Developer Platform🛡️ D56.03K @CoinbaseDev192 8 18.01K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish OGAudit | Track Crypto Safely FA_Analyst OnChain_Analyst C22.96K @OGAudit

OGAudit | Track Crypto Safely FA_Analyst OnChain_Analyst C22.96K @OGAudit OGAudit | Track Crypto Safely FA_Analyst OnChain_Analyst C22.96K @OGAudit

OGAudit | Track Crypto Safely FA_Analyst OnChain_Analyst C22.96K @OGAudit 12 3 1.00K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish

12 3 1.00K Original >Trend of FIL after releaseBullish